Amendment 1/2024: Due to the rapid pace in development of generative AI tools, we urge the reader to take note of the original publication date of the following article. The info presented here might be vastly out of date either partially or in full.

In the following description, I will attempt to simplify artificial intelligence (AI) in the context of image generation so it is as understandable as possible. This article does not intend to be a scientific definition of the subject but rather a primer for beginning to understand a complex topic. Here we will discuss narrow artificial intelligence (or ANI), which merely runs predefined tasks according to user input. A more sophisticated AI would be Artificial general intelligence (AGI), which is only theoretical now and would be on par with human capabilities. In this text, we are further focusing on computer vision, how text-to-image -generators work, and how youth workers could leverage them for purposes of youth work.

Learning to be intelligent

What does artificial intelligence or AI mean, then? To put it simply, an AI is a computer program. Most often, AI:s are used to deal with large amounts of data. In this kind of AI:s the most common use is to recognise repeating patterns or find discrepancies in that data and make an analysis based on that. This process is called artificial intelligence because it resembles the human capabilities of deduction, combining information and creating something new based on that process.

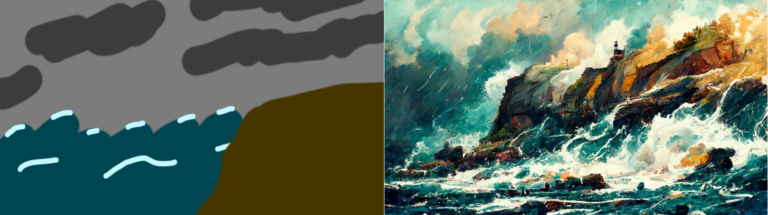

Before creating machine learning models for generating digital images, researchers developed machine vision for recognising objects and subjects in digital still and video images. This can include things such as whether the picture contains people or whether it depicts a daytime or nighttime scene. For each separate task, an AI needs to be specifically trained. For example, researchers can train a machine vision model by inputting 1000 photographs of a human face. The computer will then analyse the data by scouring the pictures for repeating patterns. These common patterns would eventually form something that the human training the algorithm would name “a face”. Then the human operators can further direct the AI to look for the same recurring patterns in different images and call them “a face”.

To slightly simplify things, machine learning means that the algorithm – or AI – is adding newly recognised patterns as a part of its existing database. This way, it can get more adept at identifying human faces in an image the next time round. This kind of AI is already present in almost every smartphone camera, where the software can recognise a face in the image and focus on it even before the user takes the picture. Researchers can use the same process to train algorithms to identify a variety of objects in images and eventually create a diverse (yet still, by definition, a narrow) AI that can find a plethora of things in existing images.

Let’s approach the topic from another perspective. An ongoing debate is whether current narrow artificial intelligences should be called augmented intelligence. A narrow AI cannot function without a human operator who defines the boundaries within which the AI operates. We must be able to ask the computer the right questions – only then can it give us the information we seek, sometimes even faster and more accurately than what we are capable of. An AI could be imbued with every possible move of a chess game, including the rules and goals and have it analyse the best possible way to win the game after every move. The computer sees the game as a changing labyrinth, where it is trying to find the shortest route out. The machine will test every possible maze turn after each move and decide the best move according to the parameters set by the user. In chess, this straightforward strategy will leave holes in the defence and allow a human player to strike back. Human creativity and adaptability to changing situations is something that narrow AI:s cannot be programmed for.

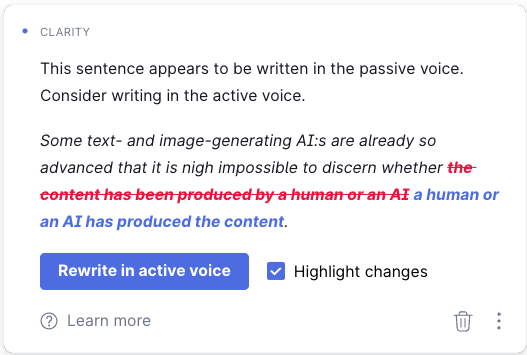

We can look at a third example. When writing this text, I have repeatedly got a wavy red line under a word I have written. The word processing software I’m using can suggest corrections and improvements to the text I’m using. (Translator’s note: To take things even further, the translation from Finnish to English has been corrected by Grammarly, which uses an algorithm to correct wording, punctuation and clarity of written text in real-time, based on my indicated writing style and target audience. Here one can see that the tools available in English are far more advanced due to the English language providing the AI:s with much more material to train on than the diminutively small Finnish language.) To my chagrin, I must note that the programme isn’t at this time able to output a whole block of text from the input “explain AI in a simplified way to youth workers”. Text-generating AI:s do exist, though. Some text- and image-generating AI:s are already so advanced that it is nigh impossible to discern whether a human or an AI has produced the content. Even these models require input, i.e., user-defined guidelines for content creation. AI:s still lack creativity and intuition, although modelling facsimiles of even these is underway.